Hamilton — Burr Dueling Grounds

Hamilton Ave.

Map / Directions to the Hamilton — Burr Dueling Grounds

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr [1]

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr both served as officers in the Revolutionary war. Hamilton spent much of the war as an aide-de-camp to General George Washington, and was an important member of what Washington called his military "family." Burr took part in several noted events of the war, including commanding a regiment at the Battle of Monmouth, which took place in Monmouth County, NJ, and was the longest continuous battle of the Revolutionary War.

After the war, Hamilton and Burr each played important roles in the early politics of the United States of America. Hamilton served as the country's first Secretary of the Treasury, where he left a lasting imprint on the financial structure of the country. Burr served as a Senator from New York, and then as Vice President.

The two men were on opposing sides politically. Hamilton was a member of the Federalist party, and Burr was a member of the Democratic-Republican party. Over time, their political rivalry turned personal, with Hamilton actively working against Burr in the Presidential election of 1800. Furthermore, Hamilton had a habit of saying and writing negative things about his political rivals, and Burr was no exception. This was to lead to their duel at Weehawken in 1804.

Dueling in the 1700's was an elaborate ritual wherein two gentlemen would work to retain their honor. However, their very definitions of words such as "gentlemen" and "honor" had connotations which are lost to us. The concepts behind dueling are so far removed from our current society that it is difficult to get our minds around it. It now seems particularly strange that two such prominent leaders as an ex-Treasury Secretary and the sitting Vice-President would settle their differences at gunpoint. It is important to remember that while their actions may seem strange to us, they were following customs that made sense to them.

Dueling was beginning to fall out of favor by the early 1800's, and was in fact illegal in New York and New Jersey. But some in the aristocracy held to the custom. In particular, military officers still participated in duels, finding it important to maintain their honor. They felt that to back down from a duel would make them appear cowardly and would cause them to lose the prestige needed for others to follow them. Hamilton and Burr had both served as officers, and were both concerned with their status in the aristocracy.

The dueling process followed a system of steps known as the code duello. Letters were sent back and forth, and the duelists appointed men known as seconds to handle the negotiations and arrangements. Most of the "affairs of honor" did not end up in bloodshed. Often the parties would reconcile during the negotiations, or on the actual dueling grounds. Within the code they followed, it was often enough for each man to maintain his honor by standing up to the duel, rather than actually killing his opponent. Sometimes a duelist would deliberately fire at the ground missing his opponent, which was known as "throwing away his shot." If neither duelist was hit in the first round of gunshots, they had the opportunity to approach each other to settle their differences verbally, rather than fire another round. However, some duels did end in death, as the one between Hamilton and Burr did.

Prelude to the Hamilton — Burr Duel

In the spring of 1804, Aaron Burr ran unsuccessfully for Governor of New York. Hamilton made efforts behind the scenes to oppose him, and was known to make derogatory statements about Burr. Comments Hamilton made about Burr at a March 1804 dinner party set in motion the events which culminated in their duel several months later.

During the dinner, Hamilton and one of the other guests, Judge James Kent, discussed Burr in negative terms. Several weeks later, on April 24, 1804, The Albany Register newspaper published a letter from Dr. Charles D. Cooper, who had attended the dinner party and heard the conversation between Hamilton and Kent.

Dr. Cooper stated that "Gen. Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared, in substance, that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government." Cooper stated further that, "I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr." [2]

The letter was printed in the April 24 edition of The Albany Register. Burr, living 150 miles away in New York City, was not aware of it until he received a copy of the newspaper in June. On June 18, Burr had a message delivered to Hamilton, who also lived in New York City, stating, "You might perceive, Sir, the necessity of a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expressions which could warrant the assertions of Dr Cooper." [3]

Hamilton sent an evasive reply to Burr two days later, saying that because Cooper's statements were not specific, he could not confirm or deny them.[4] Burr was unsatisfied with this response, and another round of letters was exchanged, as matters escalated into a duel. As was the custom, each man named a second. Seconds were appointed by the principals of the duel to handle the negotiations and arrangements. Hamilton named Judge Nathaniel Pendleton, and Burr named William Van Ness. The seconds attempted to negotiate a settlement that would prevent an actual duel, but they were unsuccessful. [5]

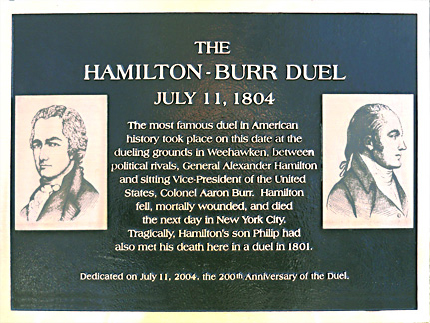

The Duel At Weehawken

July 11, 1804

Arrangements were made through the seconds to schedule the duel for the morning of July 11, 1804. The spot chosen for the duel was a small ledge on the cliffs of the Palisades on the Weehawken shore. It was a popular site for dueling because it was only accessible from the river, which kept the duelists from being disturbed. (The dueling grounds were located somewhere below the cliffs where the monument now stands, but the original site no longer exists due to development of the railroad line in 1870.) [6] Another reason for choosing a location in New Jersey was that the laws against dueling were enforced less rigorously in New Jersey than in New York.

Burr and Hamilton traveled across the Hudson River from New York City in separate boats on the morning of July 11. They were accompanied by their seconds, Pendleton and Van Ness, and the surgeon Dr. David Hosack. Eight men were employed to row the boats across the river, four to each boat. Burr's boat arrived first around 6:30 a.m.; Hamilton's arrived around 7 a.m..

Care was taken to avoid legal accountability by the non-duelists. Only the seconds left the boats to accompany Hamilton and Burr on the dueling ground; Dr. Hosack and the oarsmen remained in the boats, away from the site of the duel, so that they would not later be considered witnesses to the event.

What happened next is recorded in a statement later issued by the two seconds, Pendleton and Van Ness: [7]

"Col: Burr arrived first on the ground as had been previously agreed. When Genl Hamilton arrived the parties exchanged salutations and the Seconds proceeded to make their arrangments. They measured the distance, ten full paces, and cast lots for the choice of positions as also to determine by whom the word should be given, both of which fell to the Second of Genl Hamilton. They then proceeded to load the pistols in each others presence, after which the parties took their stations. The Gentleman who was to give the word, then explained to the parties the rules which were to govern them in firing which were as follows: The parties being placed at their stations The Second who gives the word shall ask them whether they are ready—being answered in the affirmative, he shall say 'present' after which the parties shall present & fire when they please. If one fires before the other the opposite second shall say one two, three, fire, and he shall fire or loose his fire. And asked if they were prepared, being answered in the affirmative he gave the word present as had been agreed on, and both of the parties took aim, & fired in succession, the Intervening time is not expressed as the seconds do not precisely agree on that point. The pistols were discharged within a few seconds of each other and the fire of Col: Burr took effect; Genl Hamilton almost instantly fell. Col: Burr then advanced toward Genl H——n with a manner and gesture that appeared to Genl Hamilton’s friend to be expressive of regret, but without Speaking turned about & withdrew. Being urged from the field by his friend as has been subsequently stated, with a view to prevent his being recognised by the Surgeon and Bargemen who were then approaching. No farther communications took place between the principals and the Barge that carried Col: Burr immediately returned to the City. We conceive it proper to add that the conduct of the parties in that interview was perfectly proper as suited the occasion."

(As noted in their statement, Pendleton and Van Ness disagreed on the exact details of the shots being fired, and so left those details out of their joint statement. They would each later issue individual statements regarding their perceptions of those moments when the shots were fired. The main difference in their accounts pertains to whether Hamilton fired first, and if Hamilton actually intended to shoot at Burr or throw away his shot. There has been much speculation as to this over the past two centuries, but ultimately it is impossible to know exactly what occurred in the moments the shots were fired, or what the duelists were thinking.) [8]

Dr. Hosack was called to attend to Hamilton but found him in mortal condition. The Doctor later wrote the following description of the emotional scene: [9]

"When called to him, upon his receiving the fatal wound, I found him half sitting on the ground, supported in the arms of Mr. Pendleton. His countenance of death I shall never forget. He had at that instant just strength to say, 'This is a mortal wound, Doctor;' when he sunk away, and became to all appearance lifeless. I immediately stripped up his clothes, and soon, alas! ascertained that the direction of the ball must have been through some vital part. His pulses were not to be felt; his respiration was entirely suspended; and upon laying my hand on his heart, and perceiving no motion there, I considered him as irrecoverably gone. I however observed to Mr. Pendleton, that the only chance for his reviving was immediately to get him upon the water. We therefore lifted him up, and carried him out of the wood, to the margin of the bank, where the bargemen aided us in conveying him into the boat, which immediately put off. During all this time I could not discover the least symptom of returning life. I now rubbed his face, lips, and temples, with spirits of hartshorne, applied it to his neck and breast, and to the wrists and palms of his hands, and endeavoured to pour some into his mouth. When we had got, as I should judge, about 50 yards from the shore, some imperfect efforts to breathe were for the first time manifest: in a few minutes he sighed, and became sensible to the impression of the hartshorne, or the fresh air of the water: He breathed; his eyes, hardly opened, wandered, without fixing upon any objects; to our great joy he at length spoke: 'My vision is indistinct,' were his first words. His pulse became more perceptible; his respiration more regular; his sight returned. I then examined the wound to know if there was any dangerous discharge of blood; upon slightly pressing his side it gave him pain; on which I desisted."

Each man was rowed back to New York City. Hamilton was in great pain; the bullet had fractured one of his ribs, passed through his liver and diaphragm, and lodged in his spine. [10] He was taken to the home of his friend William Bayard. He died there the following afternoon, accompanied by his wife and other family and friends.

A great uproar in public opinion occurred in New York City against Burr over Hamilton's death. Fearing prosecution, Burr fled from New York City on July 22. He first headed south from New York by boat to Perth Amboy, [11] where he spent the night at a friend's house before heading on to Philadelphia. Burr escaped prosecution, and he returned to Washington D.C. later that year to finish out his term as Vice President. He died thirty-two years after the duel, on September 14, 1836, and is buried in Princeton.

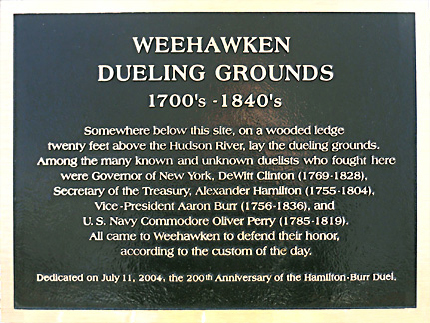

The Dueling Site and Monuments [12]

The first monument to commemorate the duel was erected on the dueling grounds in 1806. By 1821, it had been taken apart and removed by souvenir hunters. Other small markers later appeared at the dueling grounds. The site was disturbed in 1858 when a road was cut through it. In 1870, the Weehawken shoreline was reconfigured for the railroad tracks, and the dueling ground site was obliterated. In 1894, a stone bust of Hamilton was placed at the site of the current monument. It was ruined by vandals in 1934.

The bronze statue of Hamilton which stands here today was sculpted by John Rapetti in 1935. Rapetti was born in Italy and later spent time in France, where he was one of the sculptors who worked on the Statue of Liberty. He came to America in 1899 and lived for many years in Weehawken. Rapetti also sculpted the Weehawken World War I Memorial, located on J F Kennedy Blvd, about 750 feet north of the Hamilton bust. He died at his home in Weehawken in 1936 at age 74.

Behind the base of the Hamilton bust there is a boulder which folklore claimed Hamilton rested on after being hit in the duel. There is, however, no historical basis for the story; none of the original eye-witness accounts of the duel make any mention of Hamilton resting on a boulder. The boulder does have historical value, whether or not Hamilton rested on it, because it is a surviving physical connection to the original dueling grounds.

There is a small park called Hamilton Park located next to the monument. The park offers a great place to enjoy the fantastic view of the Manhattan skyline.

Other Historic Sites in New Jersey Which Are Associated with Hamilton and Burr

Hamilton and Burr each had strong biographical connections to New Jersey. Some of the other New Jersey historical sites related to Hamilton and Burr are listed below. Follow the links for more information about these historic sites.

Other New Jersey historic sites related to Alexander Hamilton • The site of the Old Academy in Elizabeth, which both Hamilton and Burr attended. • The site of Alexander Hamilton's artillery battery in New Brunswick in December 1776. • The site of the Dr. Hezekiah Stites House in Cranbury, where Hamilton met with Lafayette prior to the Battle of Monmouth. • The Great Falls in Paterson, a spot Hamilton visited in 1778 with Washington and Lafayette. Hamilton later played an important role in developing Paterson as an industrial city. There is a statue of him at the Great Falls. • Ford Mansion in Morristown, where Hamilton stayed with Washington in winter 1779-1780. • The Schuyler-Hamilton House in Morristown, where Hamilton courted his future wife Betsey Schuyler in 1779-1780. • Dey Mansion in Wayne, where Hamilton stayed with Washington in 1780. • A magnificent statue group of Hamilton, Washington, and Lafayette in Morristown. |

Other New Jersey historic sites related to Aaron Burr • Burr was born February 6, 1756, in Newark, NJ. • The site of the Old Academy in Elizabeth, which both Burr and Hamilton attended. • Burr attended Princeton University. His father had served as president of the University. • A sign in Paramus commemorates Burr's presence there in 1776. • Burr commanded a regiment at the Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778. • The Hermitage in Ho-Ho-Kus, where Burr met Theodosia Prevost in 1778. The couple were married in the house in 1782. • Solitude House in High Bridge, which Burr visited. • The Old Stone House in Ramsey, which Burr may have visited. • Burr arrived at Perth Amboy eleven days after his duel with Alexander Hamilton. • Burr died September 14, 1836. His gravesite is in Princeton Cemetery. |

Other New Jersey historic sites related to Alexander Hamilton • The site of the Old Academy in Elizabeth, which both Hamilton and Burr attended. • The site of Alexander Hamilton's artillery battery in New Brunswick in December 1776. • The site of the Dr. Hezekiah Stites House in Cranbury, where Hamilton met with Lafayette prior to the Battle of Monmouth. • The Great Falls in Paterson, a spot Hamilton visited in 1778 with Washington and Lafayette. Hamilton later played an important role in developing Paterson as an industrial city. There is a statue of him at the Great Falls. • Ford Mansion in Morristown, where Hamilton stayed with Washington in winter 1779-1780. • The Schuyler-Hamilton House in Morristown, where Hamilton courted his future wife Betsey Schuyler in 1779-1780. • Dey Mansion in Wayne, where Hamilton stayed with Washington in 1780. • A magnificent statue group of Hamilton, Washington, and Lafayette in Morristown.   Other New Jersey historic sites related to Aaron Burr • Burr was born February 6, 1756, in Newark, NJ. • The site of the Old Academy in Elizabeth, which both Burr and Hamilton attended. • Burr attended Princeton University. His father had served as president of the University. • A sign in Paramus commemorates Burr's presence there in 1776. • Burr commanded a regiment at the Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778. • The Hermitage in Ho-Ho-Kus, where Burr met Theodosia Prevost in 1778. The couple were married in the house in 1782. • Solitude House in High Bridge, which Burr visited. • The Old Stone House in Ramsey, which Burr may have visited. • Burr arrived at Perth Amboy eleven days after his duel with Alexander Hamilton. • Burr died September 14, 1836. His gravesite is in Princeton Cemetery. |

The Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society hosts an event to commemorate the duel each July.

Click here for information about this and other upcoming events.

1. ^ In addition to the contemporary sources listed in the following source notes, some information for this page, including biographical information and details surrounding the duel, was drawn from:

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: The Penguin Group, 2004) particularly pages 680-709

Nancy Isenberg, Fallen Founder — The Life of Aaron Burr (New York: Viking, 2007) particularly pages 256-2692. ^ “Enclosure: Charles D. Cooper to Philip Schuyler, [23 April 1804],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0203-0002 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0203-0002. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 243–246.]3. ^ “To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr, 18 June 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0203-0001 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0203-0001. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 242–243.]4. ^ “From Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, 20 June 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0205 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0205. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 247–249.]5. ^ These other letters were exchanged between Hamilton and Burr during this time:

• “To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr, 21 June 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0207 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0207. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 249–251.]• “From Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, 22 June 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0210 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0210. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 253–254.]• “To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr, 22 June 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0212 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0212. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 255–256.]Additional letters involving communications between the seconds are also available at the Founders Online / National Archives website:

6. ^ For details, see:

Thomas R. Flagg, An Investigation into the Location of the Hamilton Dueling Ground (Weehawken Historical Commission, 2004)

Available as a PDF on the Weehawken Historical Commission website here7. ^ “Joint Statement by William P. Van Ness and Nathaniel Pendleton on the Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, [17 July 1804],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0275 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0275. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 333–336.]8. ^ The individual statements by the two seconds are available to be read at the Founders Online / National Archives website:

• “Nathaniel Pendleton’s Amendments to the Joint Statement Made by William P. Van Ness and Him on the Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, [19 July 1804],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0277 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0277. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 337–339.]• “William P. Van Ness’s Amendments to the Joint Statement Made by Nathaniel Pendleton and Him on the Duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, [21 July 1804],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0278 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0278. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 340–341.]9. ^ “David Hosack to William Coleman, 17 August 1804,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0280 http://founders.archives.gov/

documents/Hamilton/

01-26-02-0001-0280. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 26, 1 May 1802 – 23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979, pp. 344–347.]10. ^ The specifics of the wounds were drawn from notes made by Doctor Hosack, which are quoted in the Authorial notes at the bottom of the page at the Founders Online, National Archives listed in Source Note 9

11. ^ See the Perth Amboy page of this website for more information and accompanying source note

12. ^ Information for this section was drawn from the following document, which is recommended to those looking for more details of the monument's history:

Willie Demontreux, The Changing Face of the Hamilton Monument (Weehawken Historical Commission, 2004)

Available as a PDF on the Weehawken Historical Commission website hereBiographical details about John Rapetti were drawn from :

"Heart Attack is Fatal to Rapetti, Sculpture / Native Of Italy Helped To Mould Statue Of Liberty" Wilmington Morning News, [Wilmington, Delaware] June 23, 1936, Page 1▸ The base of the bronze bust of Hamilton bears an inscription which reads, "ERECTED BY THE HAMILTON MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION 1935."