Cannonball House

126 Morris Ave.

Map / Directions to the Cannonball House

Map / Directions to all Springfield Revolutionary War Sites

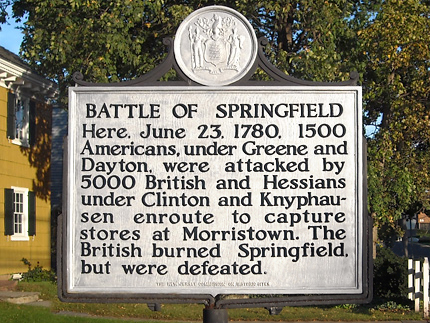

The Battle of Springfield, June 23, 1780

In June of 1780, Washington and his army were encamped at Morristown, where they had been all through the brutal winter of 1779/1780. The winter had been the worst of the century. There were twenty-eight snowstorms, and temperatures were so continuously cold that, for the only time in recorded history, the waters around New York City froze over and were closed to shipping for weeks at a time. [1] In the midst of these extreme weather conditions, the soldiers had to build their own huts and endure a serious shortage of food. The number of Washington's troops had dwindled, and the army's weapons and supplies were not sufficiently protected. The weather and lack of food over the winter has also cost the army most of their horses, which would hinder their ability to move their supplies to safety.

Two attempts were made in June 1780 by British and Hessian forces to invade New Jersey, attack Washington's troops at Morristown, and seize the vulnerable supplies. (Hessians troops were mercenary troops hired by the British to fight with them against the Americans in the Revolutionary War). Beginning with landing troops from Staten Island at Elizabethtown, they planned to move west through a gap in the Watchung Mountains with the intent to attack Washington at Morristown.

It can be hard for us living in the 21st century to visualize the importance of the Watchung Mountains during the Revolutionary War. Over two centuries of development and highway building have changed the visible landscape, and these changes allow us to easily drive over mountains which were once major obstacles to transportation and movement. For Washington's troops encamped at Morristown, the three ridges of the Watchung Mountains provided layers of protection that stretched for over 40 miles from Mahwah to Somerset County.

A gap in the Watchung Mountains known as Hobart Gap provided the one easy route to Washington's troops at Morristown. Hobart Gap was the last militarily defensible position between Elizabeth and Morristown; if the British troops could make it past Hobart Gap, they would have an easy path to Morristown to capture Washington's arms and supplies. Today, Route 24 passes through Hobart Gap in the Watchung Mountains, as does Morris Ave. in Springfield, and Millburn Ave. in Millburn. Modern development and work on the highway, including raising the elevation of this part of the highway with landfill, make it hard for our modern eyes to envision Hobart Gap as it was in the 1700's, but its legacy endures in the name of Hobart Gap Road in Summit, which passes over Rt 24.

The first attempt to invade and move through Hobart Gap began when British and Hessian troops landed at Elizabethtown on June 6, 1780. The following day, the invading forces made it as far as the village of Connecticut Farms (now Union Township), in what is known as the Battle of Connecticut Farms. Details about the Battle of Connecticut Farms can be found on the Union page of this website.

Another attempt to invade New Jersey and attack Washington at Morristown was made on June 23, resulting in the Battle of Springfield. The attacking force consisted of 5000 British and Hessian troops under the command of British General Henry Clinton and Hessian General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. 1500 Continental troops under General Nathanael Greene and about 500 New Jersey Militia successfully defended against the attack and kept the invasion from reaching Hobart Gap and on to Washington's supplies at Morristown. However, despite the American victory, the battle brought great tragedy to the citizens of Springfield; when retreating, the British and Hessian forces burned most of the buildings in Springfield. The Cannon Ball house was one of only four houses to survive unburned. After the Battles of Connecticut Farms and Springfield, British General Henry Clinton changed his strategy. No more attempts were made to invade New Jersey, and the Battle of Springfield became the last major battle fought in the North. The emphasis of the fighting shifted to the southern states, culminating in the decisive Battle of Yorktown sixteen months later on October 19, 1781. [2]

More details of the Battle of Springfield are described in the following entries.

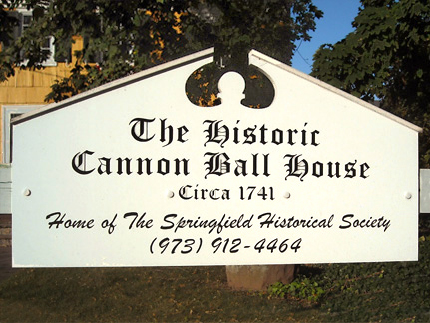

The Cannon Ball House

This house is known as the Cannon Ball House because it was hit by a cannon ball during the Battle of Springfield. Interestingly, it was hit on the side of the house facing west, which means that it was struck by a ball fired from an American cannon firing at the invading forces. The ball itself lodged in the wall where it remained for almost a century and a half. In 1924, construction work was done on the house to build a cellar. In the process, the main part of the house had to be raised, and the cannon ball fell out. The original cannon ball is on display inside the house. A replica ball hangs on a chain on the side of the house to mark the site where the house was hit. [3]

The Cannon Ball House was built circa 1741. It was owned by a doctor named Jonathan Dayton, who was a Revolutionary War soldier. He died August 16, 1778, almost two years before the Battle of Springfield. (He is buried at the Presbyterian Gateway Cemetery - see entry below on this page.) His widow Keziah (née Miller) lived in the house after Jonathan's death, and she was here at the Battle of Springfield. Jonathan had a nephew, also named Jonathan Dayton, who was a signer of the Constitution. Springfield's Jonathan Dayton High School is named for the Jonathan who signed the Constitution. [4]

Colonel Israel Angell Memorial

Morris Ave.

Map / Directions to the Colonel Israel Angell Memorial

Map / Directions to all Springfield NJ Revolutionary War Sites

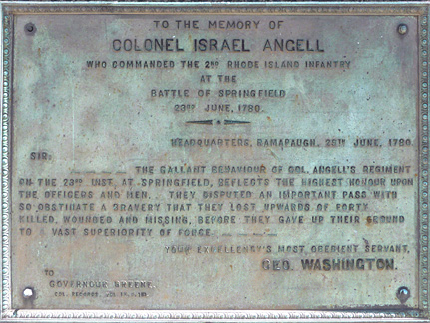

A plaque on the Morris Avenue Bridge over the Rahway River is dedicated to Colonel Israel Angell. Angell commanded the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry, who were noted for their defense of a bridge at this location over the Rahway River during the Battle of Springfield. Angell and his men were the first line of defense for Springfield, and they held off the British advance at the bridge for more than a half hour before falling back into Springfield, despite being outnumbered five to one. [5] A plaque on the modern bridge here pays tribute to Colonel Angell and his troops.

While the main attack into Springfield came over this bridge, the right column of British troops made an attempt to reach Springfield by Vauxhall road over a bridge over a different branch of the Rahway River, through what is now Millburn. Details about this part of the Battle of Springfield can be found on the Millburn page of this website.

After the Battle, General Washington wrote to Governor William Greene of Rhode Island to acknowledge the contributions of these Rhode Island soldiers, and their state in general: (Portions of the following text are quoted on the plaque) [6]

"The gallant behaviour of Colonel Angell's regiment on the 23d inst., at Springfield, reflects the highest honor upon the officers and men. They disputed an important pass with so obstinate a bravery that they lost upwards of forty in killed, wounded and missing, before they gave up their ground to a vast superiority of force.

"The ready and ample manner in which your state has complied with the requisitions of the committee of co-operation, both as to men and supplies, entitles her to the thanks of the public, and affords the highest satisfaction to, sir,

"Your Excellency's most obedient servant, GEO. WASHINGTON"

If you walk down Washington Ave. along the river, about 150 feet from this bridge there is a boulder with a plaque paying tribute to "Those brave men of the Jersey Militia and Continental Army who fought at the Battle of Springfield."

Presbyterian Church

210 Morris Ave.

Map / Directions to Springfield Presbyterian Church

Map / Directions to all Springfield Revolutionary War Sites

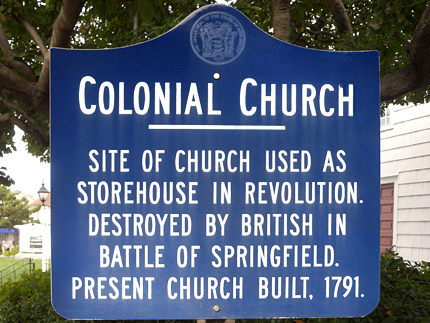

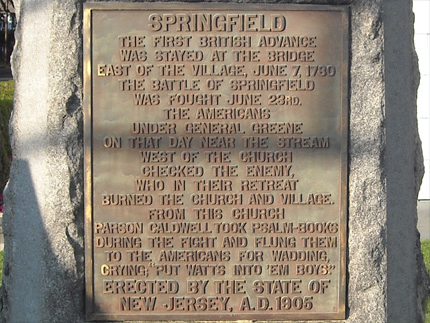

An earlier Presbyterian church building at this site (built in 1761 or 1762) stood here at the time of the Revolutionary War, and was used as a storehouse. [7] That church building was burned by British and Hessian forces during the Battle of Springfield, along with most of the other buildings in the village. The current church was built to replace the one that was burned. An event during the battle involving the previous church building has become legendary, and it is one of the most notable New Jersey stories from the Revolutionary War. The story centers on the fascinating personality of Reverend James Caldwell.

Reverend James Caldwell had an interesting Revolutionary War history, and has connections to a number of historic sites throughout Union and Essex County. He was instrumental in forming the Presbyterian Church in Caldwell, and the town of Caldwell was named for him. When the Revolutionary War began, he was devoted to the cause of Independence. Known as the "Fighting Chaplain," he served as both an army chaplain and assistant quartermaster general during the Revolutionary War. He was the pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Elizabethtown, and that church and his home were burned by British troops during a January 25, 1780 raid on Elizabethtown. With their home and church burned, James, his wife Hannah and their nine children moved to a parsonage in Connecticut Farms (now Union), and James preached at the church in Connecticut Farms. Sadly, his wife Hannah was killed when she was struck by a bullet fired by a British soldier on June 7, 1780, during of the Battle of Connecticut Farms. Just sixteen days later, James took part in the fighting at the Battle of Springfield. [8]

During the Battle of Springfield, some soldiers ran low on wadding for their muskets, and called out for more wadding. (When firing Revolutionary War era muskets, gunpowder was wrapped in paper. The paper was bit open, and the gunpowder poured in. The paper was then pushed into the musket for use as wadding, to steady the shot.) Reverend Caldwell was riding around the fighting area, encouraging the soldiers. On hearing about the need for wadding, Reverend Caldwell headed on his horse to the church and grabbed a stack of hymn-books written by the then well-known hymn-writer Isaac Watts. He rode back to the bridge, and as he threw the hymn books to the soldiers to use the pages for wadding, as he shouted, "Give 'em Watts, boys" and/or "Put Watts into 'em boys." [9]

Caldwell's shouts of "Give em Watts boys." became the most famous part of the story, and later the subject of a poem by Brette Harte. [10] However, what stands out most to me is the thought of just how personal this fight must have been to Caldwell. Within the previous half year, British troops had burned two of his houses and two churches he preached in. They had also killed his wife, leaving the Caldwell's children without a mother. One can only imagine his feelings that day as he encouraged the American soldiers to shoot British soldiers.

Unfortunately, the tragedies that had followed the Caldwell family throughout the war were not over. Just a year and a half after Hannah's death, James himself was killed by an American sentry in 1781, and their nine children were left orphaned. The sentry, James Morgan, was tried at the Westfield Presbyterian Church. He was found guilty and then hanged at a site known as Gallows Hill in Westfield. Both James and Hannah Caldwell are buried in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Elizabeth. [11]

Presbyterian Church Cemetery

Church Mall

Map / Directions to the Presbyterian Church Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Springfield Revolutionary War Sites

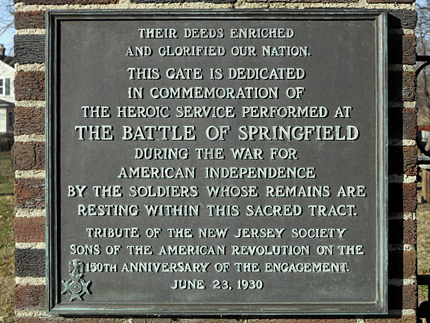

The Presbyterian Church's cemetery, located across Church Mall from the church, contains the graves of at least thirty-one Revolutionary War soldiers. A plaque at the gate pays tribute to "the heroic service performed at The Battle Of Springfield, during the war for American Independence by the soldiers whose remains are resting within this sacred tract." [12]

The Revolutionary War soldiers known to be buried here are: [13]

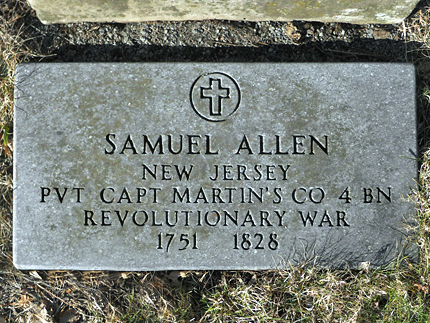

Samuel Allen

1751-1828

Private, Captain Martin's Co., 4th Battalion

Samuel Bailey

Died April 28, 1815

David Ball

1756-1805

Private, New Jersey Militia

Uzal Ball

Died April 9, 1799 "in the 52nd year of his age"

Henry Butterworth

Died January 2, 1821

Thomas Cooper

1745-1811

Somerset County Troops

Isaac Denman

Died October 29, 1791

Matthias Denman

Jan. 22, 1841

Phillip Denman

1749-1825

Private, Essex County NJ Militia

Stephan Denman

Died October 9, 1824

Aaron Edwards

Died September 15, 1804

Nathaniel Edwards

Died January 15, 1804

Thomas Gardner Jr.

1752-1804

Private, Pike's Company 2 US Levies

William Gardner

1769-1808

Private, 2nd Regiment NJ Infantry

Isaac Halsey

Died April 26, 1820

Joseph Halsey

1730-1813

Sgt., Morris County Eastern Battalion,

NJ Militia

Aaron Hand

February 23, 1764-July 27, 1842

Private, Morris County Troops

David Hand

Died February 11, 1832

Elijah Lyon

1764-1828

Private, New Jersey Militia

Benjamin Meeker

1746-1813

Essex County Troops

John Meeker

Died October 12, 1800

Timothy Miller

Died February, 1788

Benjamin Morehouse

1752 - 1820

Private, Capt. J. Pierson's Co.,

2nd Regt., NJ Militia

Isaac Reeve

1745-1785

Captain, NJ Militia

Benjamin Scudder

June 6, 1733 - February 18, 1822

Essex Militia

Walter Smith

Died October 14, 1820, Aged 86

Thomas Taylor

Died November 2, 1784

Joseph Tucker

Died February 25, 1825, Aged 78

Daniel Vreeland

1757-1828

Private, NJ Militia

Caleb Woodruff

1755-1834

Private, NJ Militia

Stephen Woodruff

Died March 29, 1789, Aged 57

Battle Ground Cemetery

Owned by the Church & Cannon Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

39 Mountain Ave. /

Up a short set of stairs from street level

Map / Directions to this Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Springfield Revolutionary War Sites

A short walk from the Presbyterian Church is this smaller cemetery, which is up a short set of stairs from street level. It contains a monument "To the memory of the patriots who fell at Springfield, June 23, 1780," [14] and the graves of at least five Revolutionary War soldiers: [15]

Jacob Brookfield

1722 -1782

Captain - 1st Regiment NJ Militia

Joseph Horton

Died September 7, 1807, Age 71

Captain

Daniel Reeve

1758 - 1780

Private, 2nd Regiment NJ Militia

Isaac Reeve

1745 - 1780

Captain, NJ Militia

Abraham Woolley

1756-1812

Captain - NJ Militia

Presbyterian Gateway Cemetery

101 Taft Ln.

Map / Directions to the Presbyterian Gateway Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Springfield Revolutionary War Sites

The Presbyterian Gateway Cemetery is the burial place of Captain Eliakim Littell (1744 - 1805), who fought at the Battle of Springfield. His original gravestone is gone, but there is a monument to his memory. One side of the monument quotes the inscription from his original gravestone: "In defense of American Liberty he dared to oppose George the Tyrant of England, an enemy to the rights of mankind." [16]

Also buried here is Jonathan Dayton, a Revolutionary War veteran who died August 26, 1778. Dayton owned the house which was hit by a cannon ball in the Battle of Springfield. At the time of the Battle of Springfield, he had been dead for nearly two years, and his widow Keziah was living at the house. [17]

1. ^ David M. Ludlum Early American Winters 1604 - 1820 (Volume I) (Boston: American Meteorological Society, 1966) p. 111 - 133

• This book contains a wealth of information about the weather for the winter of 1779-1780. Based on contemporary sources, it has day-by-day weather records for not only Morristown and New York City, but also New Haven, CT; Trappe, PA; and Westborough, MA. This book is long out of print, and it may be difficult to locate a copy. There are non-circulating reference copies of both volumes at the Morristown & Morris Township Library, which is where I located it.

• The book's author David M. Ludlum was a weather historian from New Jersey (born in East Orange, died in Princeton). For more information about Ludlum's life, see the interesting obituary which appeared for him in The New York Times when he died in 1997.2. ^ Thomas Fleming, The Forgotten Victory (New York: Reader's Digest Press, distributed by E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1973)

• Fleming's book was my main source of information for the Battle of Connecticut Farms and the Battle of Springfield. The book is recommended to those looking for an in-depth account of the battles.

• Fleming also created a condensed version of his book, which was published in 1974 as a booklet called The Battle of Springfield. The booklet was number eight of a twenty-eight booklet series called New Jersey's Revolutionary Experience, published by the New Jersey Historical Commission to commemorate the Bicentennial. A PDF of The Battle of Springfield booklet is available on the New Jersey State Library website here.3. ^ Information about the cannon ball from an information sheet with its display inside the house, and further discussed with the docents.

4. ^ Information about the history of the house and Jonathan and Keziah Dayton was drawn from the Welcome to Cannon Ball House (Circa 1741) Springfield, NJ pamphlet available at the Cannon Ball House.

5. ^ Thomas Fleming, The Forgotten Victory (New York: Reader's Digest Press, distributed by E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1973) p. 239-264

• The time for the defense of the bridge is given in some accounts as 40 minutes. In Fleming's book, he writes on page 262 "for more than twenty-five minutes Colonel Angell and his men fought five times their number to a standstill." He then goes on to describe the story about Reverend Caldwell (see source note # 1 below), before the Angell's troops falling back. So it appears that he is not stating that 25 minutes was the total time.6. ^ The text of Washington's letter, as well as the full text of a resolve passed several days later by the Rhode Island General Assembly to honor Colonel Angell's regiment, can be found in:

Louise Lewis Lovell, Israel Angell - Colonel of the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment (The Knickerbocker Press, 1921) p. 168 -170

This book available to be read at the Internet Archive here

• In the book's source footnote, it states, "This letter as well as the Resolve given in the text, is from Records of Rhode Island 9:147, 151"7. ^ History of the First Congregation of the Presbyterian Church at Springfield on the Springfield Presbyterian Church website

8. ^ More details about the events mentioned in this paragraph and accompanying source notes can be found in the entries linked in the text to the Caldwell, Elizabeth and Union pages of this website.

9. ^ Thomas Fleming, The Forgotten Victory (New York: Reader's Digest Press, distributed by E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1973) 262-263

• In Fleming's source notes he lists Washington Irving, Life of George Washington, Volume IV (New York, 1857) as a source.

Fleming also explains, "[Irving's book] is the earliest reference I have been able to find for this story, which also is a strong oral tradition of the battle. Irving spent a good deal of time in New Jersey, and his biography of Washington was a serious historical effort. In 1857, there were still many men alive in New Jersey whose fathers had fought at Springfield. This convinces me that the story is substantially true."Fleming's account in The Forgotten Victory adds details to that don't appear in Irving's one paragraph account, and so must have had other unlisted sources. Irving's short account can be read at the Internet Archive here.

One specific detail is added by Fleming that I have left out of the entry above. Fleming specifies that the soldiers who called out for wadding were Colonel Angell's men who were defending the bridge, and that a messenger was sent into town who encountered Caldwell on horseback and told him of the need for wadding. This detail does not occur in some of the other accounts I read of the "Give 'em Watts" story, and do not occur in the Irving account that Fleming lists as his source. Because of my uncertainty about this detail, I chose to leave it out of the main entry, but mention it here in the source notes.

• Different accounts of the incident state that Watts said either "Give 'em Watts, boys," or "Put Watts into 'em boys" or both, or some variation of one or both. For example, Fleming quotes "Give 'em Watts, boys" and Irving quotes "Now, put Watts into them, boys!" It would seem impossible to determine was his exact words were in the middle of the battle. "Give 'em Watts, boys" appears to be the most quoted version. It certainly sounds the catchiest to me.

10. ^ The poem Caldwell of Springfield (New Jersey, 1780) was written by poet and author Brett Harte (1836– 1902), and originally published in the New York Tribune on July 4, 1873.

Gary Scharnhorst, Bret Harte: A Bibliography (Lahham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1995) p. 53 Available at Google Books hereThe entire text of the poem follows. Note that Brett Harte takes some license with the details. For example, the poem makes it appear that Hannah Caldwell's death occurred on the same day as the Battle of Springfield. In fact, Hannah's death had occurred on June 7, 1780 at the Battle of Connecticut Farms; the Battle of Springfield occurred sixteen days later on June 23, 1780. Also the "Broke the door, stripped the pews" is a bit of poetic license.

~ Text of poem from The Writings of Bret Harte, Volume VII (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1904) p. 31 Available to be read at Google Books hereCaldwell of Springfield

(New Jersey, 1780)HERE's the spot. Look around you. Above on the height

Lay the Hessians encamped. By that church on the right

Stood the gaunt Jersey farmers. And here ran a wall,—

You may dig anywhere and you 'll turn up a ball.

Nothing more. Grasses spring, waters run, flowers blow,

Pretty much as they did ninety-three years ago.Nothing more, did I say? Stay one moment: you've heard

Of Caldwell, the parson, who once preached the Word

Down at Springfield? What, no? Come—that 's bad: why he had

All the Jerseys aflame! And they gave him the name

Of the "rebel high-priest." He stuck in their gorge,

For he loved the Lord God,—and he hated King George!He had cause, you might say! When the Hessians that day

Marched up with Knyphausen they stopped on their way

At the "farms," where his wife, with a child in her arms,

Sat alone in the house. How it happened none knew

But God—and that one of the hireling crew

Who fired the shot! Enough!—there she lay,

And Caldwell, the chaplain, her husband, away!Did he preach — did he pray? Think of him as you stand

By the old church to-day, — think of him and his band

Of militant ploughboys! See the smoke and the heat

Of that reckless advance, of that straggling retreat!

Keep the ghost of that wife, foully slain, in your view,—

And what could you, what should you, what would you do?Why, just what he did! They were left in the lurch

For the want of more wadding. He ran to the church,

Broke the door, stripped the pews, and dashed out in the road

With his arms full of hymn-books, and threw down his load

At their feet! then above all the shouting and shots

Rang his voice,—"Put Watts into 'em,—Boys, give 'em Watts!"And they did. That is all. Grasses spring, flowers blow,

Pretty much as they did ninety-three years ago.

You may dig anywhere and you'll turn up a ball,—

But not always a hero like this —and that 's all.

11. ^ More details about the events mentioned in this paragraph and accompanying source notes can be found in the entries linked in the text to the Westfield and Elizabeth pages of this website.

12. ^ Plaque states "Tribute of the New Jersey Society Sons of the American Revolution on the 150th Anniversary of the engagement, June 23, 1930."

13. ^ Names, dates, and rank information from gravestones and markers in the cemetery, and from a list posted inside the Cannon Ball House. Some cross-checking of this information was done with the D.A.R. Genealogical Research System database.

14. ^ Monument erected by the New Jersey State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution - October 18, 1896.

15. ^ Names, dates, and rank information from gravestones and markers in the cemetery.

16. ^ Eliakim Littell grave monument at the Presbyterian Gateway Cemetery

17. ^Welcome to Cannon Ball House (Circa 1741) Springfield, NJ pamphlet available at the Cannon Ball House.