Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

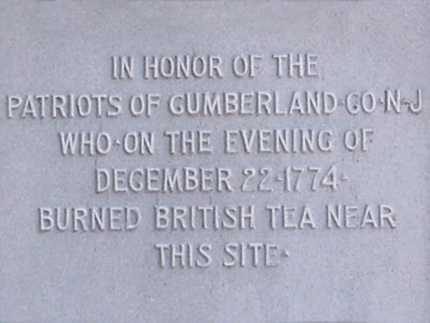

Greenwich Tea Burning Monument

Ye Greate St. and Market Ln.

Map / Directions to The Greenwich Tea Burning Monument

Map / Directions to all Greenwich Revolutionary War Sites

Prelude: The Boston Tea Party - December 16, 1773

The Boston Tea Party is one of the more iconic scenes of the Revolutionary War era. It took place a year and a half before the fighting of the war began, during the period when tensions were increasing between the British government and the thirteen British colonies in America.

On December 16, 1773, over one hundred Boston, Massachusetts citizens protested the British tax on tea by dumping tons of British tea into Boston Harbor. To punish Massachusetts for the destruction of this valuable commodity, the British government enacted a series of laws restricting the rights of Massachusetts citizens. These measures caused outrage throughout the American colonies and became known as the Intolerable Acts. [1]

As a show of support and solidarity for the citizens of Massachusetts and as a sign of resistance against British tyranny, Americans began to discourage the importing and drinking of British tea. On October 20, 1774, the Continental Congress agreed on a series of guidelines to address the current situation, which included a call to not important British goods, specifically tea. [2] Two months later, the tensions led to the destruction of another large quantity of British tea, this time in Greenwich, NJ, although the events in Greenwich are much less well known than the famous Boston Tea Party.

The Greenwich Tea Burning - December 22, 1774 [3]

Greenwich is located along the Cohansey River, which flows into the much larger Delaware River, a major route for transporting goods by boat, making this area a normal stop for ships in transit.

In mid-December of 1774, a British ship called the Greyhound was carrying a shipment of tea up the Cohansey River towards Philadelphia. Along the way, the Greyhound docked at Greenwich, and tea was hidden in the home of a local British sympathizer named Daniel Bowen.

On the night of December 22, local residents were meeting at the Cumberland County Courthouse to discuss the recent guidelines stated by the Continental Congress. During the meeting, they were made aware of the hidden tea, and a five-man committee was appointed to determine what should be done about it. While this was occurring, a group of local citizens decided to take matters into their own hands. They confiscated the tea and burned it near where the monument stands today.

Some of the tea burners faced civil and criminal charges. However, due in part to sympathies of the local citizens for the tea burners' cause, the trials were not completed.

The Monument

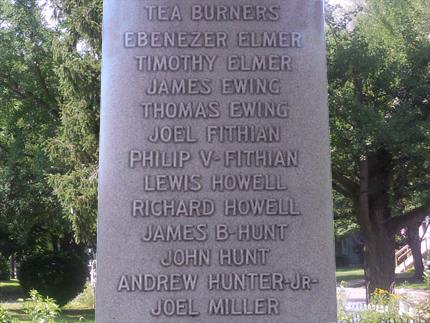

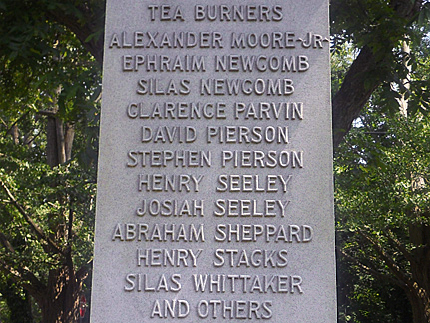

The Greenwich Tea Burners Monument was dedicated September 30, 1908. [4] As shown below, the sides of the monument list the names of the twenty-three men who are believed to have taken part in the Greenwich Tea Burning. Many of these men went on to serve militarily in the Revolutionary War, including Philip Vickers Fithian, who is discussed in the entry about his house below.

Several of the Greenwich Tea Burners went on to political success after the war. Ebenezer Elmer served in the House of Representatives. James Ewing, who is described in more detail in the James Ewing House entry lower on this page, became the mayor of Trenton. Richard Howell became the fourth elected governor of New Jersey.

Philip Vickers Fithian House

Teaburner Rd.

Map / Directions to The Philip Vickers Fithian House

Map / Directions to all Greenwich Revolutionary War Sites

This house is a private residence.

Please respect the privacy and property of the owners.

Philip Vickers Fithian was born in this house in 1747. He died in 1776 before reaching his twenty-ninth birthday. Philip experienced and accomplished much in his short life, some of which involved the Revolutionary War. [5]

Philip attended Princeton University, which was then called the College of New Jersey, in 1771-1772 to study for the clergy. He studied under the college president John Witherspoon, who would later sign the Declaration of Independence. Philip also met other future Revolutionary War figures such as James Madison, Aaron Burr, and Philip Freneau, who were attending the college as students.

After graduating, he spent some time in Virginia as a tutor and then returned to Greenwich where he became a Presbyterian minister. He preached at a number of locations, including the Greenwich Presbyterian church.

Philip was a supporter of the American cause of Independence and is believed to have been one of the Greenwich Tea Burners. There is a local tradition that the tea burners met at this house before burning the tea, but that tradition is unsubstantiated.

In 1776, he became a chaplain in the Cumberland County Militia. He traveled to New York to be with the troops there during the defense of New York. In September, he was with troops at Fort Washington in upper Manhattan. Due to crowded, unsanitary conditions, there was a great deal of disease in camp. Philip became very ill in late September, suffering with a high fever and with boils broken out over his body. He died on October 8.

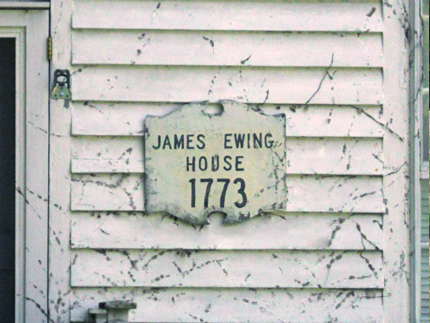

James Ewing House

903 Ye Great St.

Map / Directions to the James Ewing House

Map / Directions to all Greenwich Revolutionary War Sites

This house is a private residence.

Please respect the privacy and property of the owners.

This house, which was built in 1773, was the home of James Ewing, one of the Greenwich Tea Burners. [6] He also served as an officer in the Cumberland County Militia during the war. His brother Thomas, another tea burner, served as a surgeon in the militia. The two Ewing brothers were at Fort Washington in 1776, at the same time that Philip Vickers Fithian was there as a chaplain. [7]

Later in the war, James Ewing represented Cumberland County during the 1778 and 1779 sessions of the New Jersey General Assembly. [8] He remained politically active after the war. In 1790, President George Washington appointed him the Commissioner of Loans for New Jersey. [9] He later served as the Mayor of Trenton from 1797-1803.

In 1798, while serving as Mayor, Ewing published a twenty-eight page pamphlet titled "The Columbian Alphabet," which proposed a simplified system of spelling for the English language. He sent a copy of the pamphlet to George Washington, who was then in retirement at Mount Vernon, his home in Virginia. Washington sent Ewing the following reply: [10]

Mount Vernon 26th Feby 1799

Sir

The Columbian Alphabet which you were so polite as to send me, came safe, and for which I pray you to accept my thanks. It is curious, and if it could be introduced, might be useful for the purposes proposed; but it will be a work of time, it is to be feared, before it shall be adopted, generally. I am Sir Your most Obedt Hble Servant

Go: Washington

On December 14, less than ten months after writing this letter, George Washington died at Mount Vernon. James Ewing remained in Trenton for the rest of his life. He died October 23, 1823, and is buried at the Presbyterian Church of Trenton. His simplified method of spelling was never adopted.

Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Gravestones in the Old Presbyterian Church

The current church building, built 1834, is in the background.

Old Presbyterian Cemetery

Ye Great St. and Sheppard's Mill Rd.

Map / Directions to the Old Presbyterian Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Greenwich Revolutionary War Sites

Greenwich Presbyterian Church

The church building which stands here today was built in 1834. [11] It replaced an earlier church building which stood on the side of the street where the cemetery is. All but one of the Greenwich Tea Burners were Presbyterian and would have attended services at that earlier church building. Philip Vickers Fithian preached some sermons at the church after he became a minister. [12]

Greenwich Presbyterian Church [13]

Several of the Greenwich Tea Burners are buried in the cemetery: Thomas Ewing, Joel Fithian, James B. Hunt and Joel Miller. Philip Vickers Fithian is commemorated on one side of a Fithian family monument in the cemetery, but he is not buried here. He is probably buried in New York City, near where he died at Fort Washington, but the gravesite is unknown.

The cemetery also contains the graves of other Revolutionary War veterans, including John Bereman, Thomas Brown, Abijah Holmes, James Johnson, John Miller, Azariah More, and Enos Woodruff.

1. ^ For more information about the Boston Tea Party and about visiting the location where it occurred, see the websites of the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum and the Boston Tea Party Historical Society.

2. ^ Journals of the Continental Congress, Volume 1 (Washington D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904) Pages 75 - 80

Available to be read at Google Books here

3. ^ Four sources about the Greenwich Tea Burning are listed below in the chronological order of their publication, beginning with a newspaper article which appeared the month after the tea burning, and running up to a work published in 1908.

"Proceedings of the Inhabitants of Cumberland County, in Accordance with the Recommendations of the Continental Congress—Disapproval of the Destruction of Tea at Greenwich," Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, January 19, 1775, as reprinted in:

Frederick W. Ricord and William Nelson, Editors, Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, Volume V (Newark: Daily Advertiser Printing House, 1886)

Available to be read at Google Books hereRobert Gibbon Johnson, An Historical Account of the First Settlement of Salem, in West Jersey (Philadelphia: Orrin Rogers, 1839) Pages 123-126

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereThomas Cushing and Charles Sheppard, History of the Counties of Gloucester, Salem, and Cumberland New Jersey, Volume 2 (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1883) 536-538

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereFrank D. Andrews, The Tea-burners of Cumberland County (Vineland, NJ: Vineland Historical and Antiquarian Society, 1908)

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereFor an article about the progression of the Greenwich Tea Burning story, see:

John Fea, "Recovering Memories of a Defining Local Event: A Revolutionary-Era Tea Burning," The Readex Report, Volume 4, Issue 24. ^ Plaque on the back of the Greenwich Tea Burning Monument.

5. ^ Biographical details about Philip Vickers Fithian in this entry were drawn from:

John Fea, The Way of Improvement Leads Home - Philip Vickers Fithian and the Rural Enlightenment in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008)6. ^ Plaque on the front of the house.

7. ^ John Fea, The Way of Improvement Leads Home - Philip Vickers Fithian and the Rural Enlightenment in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) Pages 189, 194, 197, 206, 208

William S. Stryker, Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War (Trenton: Wm. T. Nicholson & Co., 1872) Pages 336, 340, 343, 365, 375 and 425

Available to be read at Google Books here

8. ^ Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the state of New-Jersey, at a Session begun at Trenton on the 27th Day of October 1778, and Continued by Adjournments (Trenton: Isaac Collins, 1779) Page 3

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereVotes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the state of New-Jersey, at a Session begun at Trenton on the 26th Day of October 1779, and Continued by Adjournments (Trenton: Isaac Collins, 1780) Page 3

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here9. ^ Two letters from Ewing to Washington petitioning for this job, as well as Washington's nomination of Ewing, are available to be read at the Founders Online / National Archives website:

“To George Washington from James Ewing, 15 January 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-04-02-0387. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 582–584.]

“To George Washington from James Ewing, 2 August 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0075. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 176–177.]

“From George Washington to the United States Senate, 6 August 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0091. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 203–204.]

10 ^ “From George Washington to James Ewing, 26 February 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0299. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 3, 16 September 1798 – 19 April 1799, ed. W. W. Abbot and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, p. 399.]

11. ^ National Register of Historic Places / Inventory - Nomination Form for the Greenwich Historic District

Available as a PDF on the National Park Service website here12. ^ John Fea, The Way of Improvement Leads Home - Philip Vickers Fithian and the Rural Enlightenment in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) Page 129, and source note 52 on page 245

13. ^ Information drawn from gravestones, markers and plaques in the cemetery.