Revell House

213 Wood St.

Map / Directions to the Revell House

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

The Revell House is maintained by the Colonial Burlington Foundation, which holds the annual Wood Street Fair.

The house is open for tours during the fair. See www.woodstreetfair.com for more information

Benjamin Franklin was one of the central figures of the Revolutionary War era. [1] He signed both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. He was a member of the Continental Congress. His diplomacy with France during the war helped to ensure French support to the America side in the war, in the form of financial loans and military troops, both of which played a crucial role in the American victory.

But it should be remembered that when the Revolutionary War began, Franklin was almost seventy years old and had already lived a full and multifaceted life. He was successful in the fields of publishing, writing, business, politics, and diplomacy. He also made important contributions to the scientific understanding of electricity with his famous kite experiment, and he invented the lightning rod, the Franklin stove and bifocals.

Throughout his long and remarkable life, Franklin went many places and did many things. And as a teenager, he took a fifty-mile walk across New Jersey which led him through Burlington, where he is believed to have stopped at the Revell House.

Benjamin Franklin was born in 1706 in Boston. At the age of twelve, he was apprenticed to his older brother Joseph in his print shop. Young Benjamin learned the printing trade, and also began his writing career for Joseph's newspaper, The Courant. However, Joseph mistreated Benjamin, and physically beat him. In 1723, when Benjamin was seventeen, he decided to run away from his brother and his apprenticeship.

He took a ship from Boston to New York City, where he hoped to find work as a printer. In New York City, he met the owner of a print shop who told him that he had no need for another worker at that time, but advised him to head to Philadelphia to find work.

Franklin traveled by boat to Perth Amboy. He then proceeded to walk fifty miles to Burlington, to take a boat to Philadelphia, located across the Delaware River. While in Burlington, he bought gingerbread and later ate dinner at a house which local tradition places as the Revell House.

Franklin described stopping at Burlington in his Autobiography: [2]

"I proceeded the next day, and got in the evening to an inn within eight or ten miles of Burlington, kept by one Dr. Brown... At his house I lay that night, and the next morning reached Burlington, but had the mortification to find that the regular boats were gone a little before my coming, and no other expected to go before Tuesday, this being Saturday; wherefore I returned to an old woman in the town, of whom I had bought gingerbread to eat on the water, and asked her advice. She invited me to lodge at her house till a passage by water should offer; and being tired with my foot traveling; I accepted the invitation. She, understanding I was a printer, would have had me stay at that town and follow my business, being ignorant of the stock necessary to begin with. She was very hospitable gave me a dinner of ox-cheek with great good will, accepting only of a pot of ale in return; and I thought myself fixed till Tuesday should come. However, walking in the evening by the side of the river, a boat came by which I found was going towards Philadelphia, with several people in her. They took me in, and, as there was no wind, we rowed all the way; and about midnight, not having yet seen the city, some of the company were confident we must have passed it, and would row no farther; the others knew not where we were; so we put toward the shore, got into a creek, landed near an old fence, with the rails of which we made a fire, the night being cold, in October, and there we remained till daylight. Then one of the company knew the place to be Cooper's Creek, a little above Philadelphia, which we saw as soon as we got out of the creek, and arrived there about eight or nine o clock on the Sunday morning, and landed at the Market Street wharf."

When Franklin did arrive in Philadelphia, he began his very successful career as a printer. Five years later, Franklin returned to Burlington for three months as part of a printing job to print paper money for New Jersey, as described in the 206 High Street Site entry below.

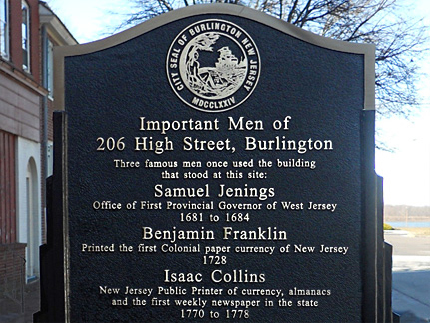

In addition to Benjamin Franklin, the "Important Men of 206 High Street" sign also commemorates Isaac Collins, who began printing New Jersey's first newspaper, The New Jersey Gazette, here in 1777.

206 High Street

Map / Directions to 206 High Street

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia in 1723, he got a job at the print shop of a man name Samuel Keimer. The following year, Franklin left Keimer's shop and returned to his home town Boston for several months. He then traveled to London where he also worked as a printer.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726, and the following year, he returned to Keimer's print shop. The now more-experienced Franklin was made the manager of the shop.

In 1728, Franklin and Keimer had an argument, and Franklin quit. However, he was lured back by Keimer, who had just received a lucrative job to print paper money for New Jersey.

The two came from Philadelphia across the Delaware River to Burlington, where they spent three months working on printing the paper currency in a building which stood at this site. [3]

Franklin described the time he spent in Burlington printing the paper currency in his Autobiography: [4]

"At Burlington I made an acquaintance with many principal people of the province. Several of them had been appointed by the Assembly a committee to attend the press and take care that no more bills were printed than the law directed. They were therefore, by turns, constantly with us, and generally he who attended brought with him a friend or two for company. My mind having been much more improved by reading than Keimer's, I suppose it was for that reason my conversation seemed to be more valued. They had me to their houses, introduced me to their friends, and showed me much civility."

The Franklin connection to Burlington continued decades later, when Benjamin's son, William Franklin, was appointed the Royal Governor of New Jersey. During the first eleven years as Royal Governor, William lived in a house in Burlington, which is described in the Site of Green Bank entry below.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars hall in Burlington stands on Riverbank Street. The street runs along the Delaware River, overlooking Pennsylvania and Philadelphia on the other side.

It stands at the site of a manor house known as Green Bank in the 1700's. (The house was demolished in 1873. [5])

From 1763 to 1774, Green Bank was the estate of the Royal Governor of New Jersey, William Franklin.

After Franklin left, a Quaker widow named Margaret Morris lived at this house with her extended family. Margaret left a diary which told of her first-hand experiences with the impact of the war in Burlington.

William Franklin [6]

William Franklin was born circa 1730, the illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin. His mother's identity is unknown, but Benjamin and his common-law wife Deborah Read raised him as their son. William was close with his father growing up and as a young man. He participated in his father's famous kite-flying electricity experiment in 1752.

William Franklin began serving as the Royal Governor of New Jersey in 1763. [7] At that time, New Jersey was still a British colony, and it had a Royal Governor who was appointed by the King of England. There were two capitals of New Jersey then, Perth Amboy in the east and Burlington in the west. During his first eleven years as governor, William lived in Burlington at Green Bank. Then in 1774, he moved to Perth Amboy to live at Proprietary House.

During William's years as Royal Governor of New Jersey, the tensions that would lead to the Revolutionary War grew throughout all thirteen colonies. Feelings were mixed, some people sided with Independence, while others remained loyal to Britain. This choosing of sides sometimes caused rifts within families, as it would within the Franklin family.

Shortly after the Revolutionary War began in 1775, Benjamin and William met to discuss their positions regarding Independence. It was clear that neither man would be swayed from the path they had chosen. Benjamin was committed to being fully politically active in the American cause of Independence; William was committed to continuing as the Royal Governor and remaining Loyal to Britain. The two met again briefly that November, which would turn out to be their last meeting until the end of the war. Each man remained true to the side they had chosen, and events were quickly developing that would soon break them apart permanently.

On June 19, 1776, eleven days before American Independence was declared, William Franklin was arrested as the Royal Governor. After his arrest, William was taken to Burlington, where he faced a hearing in front of the New Jersey Provincial Congress. William was defiant at the hearing. He rejected the authority of the New Jersey Provincial Congress and told them to "do as you please, and make the best of it." William was then taken to East Windsor, Connecticut, where he was held prisoner until he was released in a prisoner exchange in 1778. He then spent the rest of the war in British-occupied New York City. (The events surrounding William Franklin's arrest and captivity are described in greater detail in the Proprietary House entry on the Perth Amboy page.)

After the war ended, William moved to Britain, where he lived the rest of his life. Benjamin and William only saw each other one time after the end of the war, when they met in London in 1785. The purpose of that meeting was not to heal the rift between them, but to sort out some business and financial matters. The two men never reconciled as father and son, and they never spoke again. Benjamin died in Philadelphia in 1790, and William died in London in 1813.

Margaret Morris [8]

After William Franklin left Burlington for Perth Amboy in 1774, Green Bank became the home of a Quaker couple, George and Sarah Dillwyn. Sarah's sister, Margaret Morris, a widow with four children, came to live at Green Bank with them. Margaret Morris kept a diary of her experiences during 1776-1778. It is now a valuable firsthand record of the impact of the Revolutionary War in Burlington.

In December, 1776 the Revolutionary War touched directly the lives of Margaret, her children and her sister Sarah at Green Bank. (Sarah's husband George was away at the time.)

On December 11, 1776, a large group of Hessians came into Burlington. Several prominent citizens of the town came out to communicate with the Hessian officers, who agreed to not harm the town if no one in town made any resistance against them.

American forces in ships in the Delaware River fired on Burlington throughout the night, thinking that Hessians were occupying the houses.

In the morning, after the Hessians had left, the American troops came ashore at the riverbank. Margaret gave a description of what happened:

"This morning a galley [ship], with a great many men, and a number of boats, came ashore at our wharf. I ordered the children to keep within doors, and went myself down to the shore, and asked what they were going to do. They said to fire the town if the Regulars [British soldiers] entered. I told them I hoped they would not set fire to my house. "Which is your house and who are you?" I told them I was a widow, with only children in the house, and they called to others and bid them mark that house, there was a widow and children, and no men in it; "but," said they, "it is a mercy we had not fired on it last night; seeing a light there, we several times pointed the guns at it; thinking there were Hessians or Tories in it; but a hair of your head shall not be hurt by us." See how Providence looks on us. Then they offered to move my valuable goods over the river, but I pointed to the children at the door, and said; "see, there is all my treasure, those children are mine," and one who seemed of consequence, said: "Good woman, make yourself easy, we will protect you." "

The American forces then proceeded to search the town for Loyalists (Americans who remained loyal to Britain during the war, also called Tories), and specifically for those who had cooperated with the Hessians while they were in Burlington.

Margaret Morris hid a known Loyalist named Joseph Odell in a hiding space in the house. Odell, the Reverend of St. Mary's Church of Burlington, was a known Loyalist who had acted as an interpreter for Hessian Colonel von Donop during his time in Burlington. (See Old St. Mary's Episcopal Church entry below for more about Joseph Odell.)

Old St. Mary's Church

West Broad St. and Wood St.

Map / Directions to the Old St. Mary's Church

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, the reverend at Old St. Mary's Church was Jonathan Odell. When the Revolutionary War began, Odell remained loyal to Britain and King George III. He was also known for writing poetry that was pro-British and anti-Independence..

Odell's outspoken Loyalism did not go unnoticed by the Provincial Congress of New Jersey, who referred to Odell as "a person suspected of being inimical to American liberty." The Provincial Congress was the governing body of New Jersey during the early period of the Revolutionary War as the transition was made from British colony to a state of the United States of America.

On July 20, 1776, the Provincial Congress ordered Odell to sign a parole agreement that he would remain within eight miles of the Burlington County courthouse. Odell requested that he be given a different parole agreement; the Provincial Congress denied his request and ordered him to sign the original parole agreement.

When Hessians marched into Burlington in December 1776 (as described in the Margaret Morris section above), Odell acted as an interpreter with the Hessian commander, Colonel Carl von Donop. The Hessian officers did not speak English and Odell did not speak German, but both spoke French, so they were able to communicate in French. Margaret Morris noted in her diary that "The [Hessian] commandant seemed highly pleased to find a person with whom he could converse with ease and precision."

After the Hessians left Burlington, American troops came into the town and searched for locals who had collaborated with the Hessians, including Odell. Margaret Morris hid Odell in her house, and he escaped detection. Afterwards, Odell fled to New York City, which was occupied by the British.

Although Odell was able to briefly return to Burlington in January 1777, he spent most of the rest of the war behind British lines, where he continued to write pro-British poetry. After the Revolutionary War ended, he spent several months in London, before settling in New Brunswick, Canada, along with thousands of other Loyalists who settled there after the war. [9]

Services were held at Old St. Mary's Church until the construction of New St. Mary's Church in 1854. [10] New St. Mary's stands about 200 feet to the west of Old St. Mary's. The church cemetery, which contains the graves of several notable Revolutionary War figures, is located between the two buildings.

St. Mary's Church Cemetery

145 West Broad St.

Map / Directions to the St, Mary's Church Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

This cemetery is located between Old St. Mary's Church and New St. Mary's Church. It contains the graves of several notable Revolutionary War era figures, two of whom also served as Mayors of Burlington. Short bios of these four men appear below.

Joseph Bloomfield

(Oct. 18, 1753 - Oct. 3, 1823)Joseph Bloomfield was born in Woodbridge, NJ, in 1753. During the Revolutionary War, he was an officer in the Third New Jersey Regiment, beginning as a Captain and rising to the rank of Major. He also served for a time as the Judge Advocate of the Northern Army. [11] At the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, a musket ball pierced through his left arm, setting his coat and shirt on fire. After taking several months to recover from his wounds, he returned to active service and fought at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778. [12]

Joseph Bloomfield had a very successful career after the war ended. He served as the Attorney General of New Jersey from 1783-1792, as the Mayor of Burlington from 1795-1800, as the Governor of New Jersey from 1801-1812, as a Brigadier General in the War of 1812, and in the House of Representatives from 1817-1821. [13]

Joseph Bloomfield was a lifelong opponent of slavery, and he served as president of the New Jersey Society for the Abolition of Slavery. His father, Moses Bloomfield, was also an activist for abolition; he held anti-slavery meetings in his Woodbridge home where Joseph was born. [14]

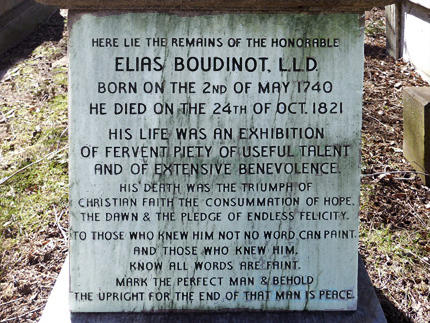

Elias Boudinot

(May 2, 1740 - October 24, 1821)

Hannah Stockton Boudinot

(July 21, 1736 - October 28, 1808)

Susan Vergereau Boudinot Bradford

(December 21, 1764 - November 30, 1854)

Elias Boudinot was a member of the Continental Congress, and he served as the President of the Continental Congress in 1782-1783. It was during this time, on October 31, 1783, that word reached the Continental Congress, who were then meeting at Nassau Hall in Princeton, that the Treaty of Paris had been signed, officially ending the Revolutionary War. [15]

After the War, Boudinot remained politically active. He represented New Jersey in the House of Representatives from March 4, 1789 - March 3, 1795. President George Washington appointed him Director of the United States Mint in October 1795.

Boudinot resigned from the United States mint in 1805 and retired to Burlington, along with his wife Hannah Stockton Boudinot and their daughter Susan Vergereau Boudinot Bradford. [16] Hannah was the sister of Richard Stockton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Susan was the widow of Revolutionary War officer William Bradford, who is described below. Hannah and Susan are also buried in this cemetery.

The house in Burlington where Elias, Hannah, and Susan lived can be seen in the Boudinot-Bradford House entry lower on this page.

William Bradford

(September 14, 1755 – August 23, 1795)

William Bradford was the son-in-law of Elias Boudinot, married to his daughter Susan. He served as an officer during the Revolutionary War. A decade after the end of the war, Bradford served an important role in the new government when he was appointed the second Attorney General of the United States by President George Washington. He served as Attorney General from January 27, 1794 until his death just over a year and a half later. [17]

Bowes Reed

(Died July 20, 1794, Aged 54)Bowes Reed played prominent roles both militarily and politically during the Revolutionary War. He served as colonel of the Burlington County militia during the Revolutionary War from 1776-1778. He resigned from the militia on March 31, 1778. Later that year, he was appointed the Secretary of State of New Jersey, a position he held until the end of the war in 1783, and then until his death in 1794. He was appointed as the Mayor of Burlington in 1784, an office which he also served in until his death. [18]

Bowes Reed had a brother named Joseph Reed, who also played a number of important roles during the Revolutionary War. Joseph served as an aide-de-camp to General George Washington, as adjutant-general of the Continental Army, as a delegate to the Continental Congress, and as the Governor of Pennsylvania. [19]

Boudinot-Bradford House

207 Broad St.

Map / Directions to the Boudinot-Bradford House

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War SitesThis house is a private residence.

Please respect the privacy and property of the owners.This house, which was built circa 1804, was the home of Elias Boudinot, who had been the president of the Continental Congress at the end of the Revolutionary War. He moved into the house when he retired from public life in 1805.

Elias lived here with his wife Hannah, who was the sister of Declaration of Independence signer Richard Stockton; and their daughter Susan, the widow of Revolutionary War officer William Bradford. [20]

Elias, Hannah, and Susan all lived in this house until their deaths. They are all buried at St. Mary's Church Cemetery. (See the St. Mary's Church Cemetery entry above.)

There are two other houses in New Jersey associated with Elias Boudinot: Boxwood Hall in Elizabeth, and the Lord Stirling / Elias Boudinot House in Chatham Township.

Bard-How House

453 High St.

Map / Directions to the Bard-How House

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

The Bard-How House is part of the Burlington County Historical Society.

For current hours and admission information, see their website:

www.burlingtoncountyhistoricalsociety.orgThis house was built circa 1743 by Bennett and Sarah Pattison Bard. In 1756, it was purchased by Samuel How, Sr. [21] In 1775-1776, How served as a delegate from Burlington County in the Provincial Congress of the United States. [22] The Provincial Congress was the governing body of New Jersey during the early period of the Revolutionary War, as the transition was made from British colony to a state of the United States of America.

Lawrence House

459 High St.

Map / Directions to the John Lawrence House

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War Sites

The Lawrence House is part of the Burlington County Historical Society.

For current hours and admission information, see their website:

www.burlingtoncountyhistoricalsociety.orgAt the time of the Revolutionary War, this was the house of John Lawrence, who earlier served as the Mayor of Burlington. [23]

When Hessians marched into Burlington in December 1776 (as described in the Margaret Morris section above), Lawrence entertained Hessian officers in this house. After the Hessians left Burlington, Lawrence was suspected of Loyalist sympathies and of having harbored the enemy. He was called before the New Jersey Council of Safety in 1777, and he was imprisoned on at least two occasions. [24]

John's son, James Lawrence, was born in this house on October 1, 1781. James went on to become an American naval officer during the War of 1812. He was mortally wounded during a naval battle during that war, and is remembered for his dying command, "Don't give up the ship."

This house has a plaque commemorating the birthplace of Captain James Lawrence, but there is no mention of his father John.

Friends Burying Ground

340 High St.

Map / Directions to the Friends Burying Ground

Map / Directions to all Burlington Revolutionary War SitesJames Kinsey, who was one of five New Jersey delegates to the First Continental Congress, is buried here.

1. ^ Biographical details of Benjamin Franklin's life were drawn mainly from:

• Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin, An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003)

• Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

2. ^ Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

In the Signet Classic paperback edition of Benjamin Franklin: The Autobiography and Other Writings this quote appears on pages 37-38.3. ^ Information for this section was drawn from:

• Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

In the Signet Classic paperback edition of Benjamin Franklin: The Autobiography and Other Writings the story appears on pages 40-69.• Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin, An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003) Pages 38-53

• The City of Burlington historic sign in the photo identifies 206 High Street as the location where Franklin printed the paper currency. Sign dedicated January 21, 2006.

4. ^ Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

In the Signet Classic paperback edition of Benjamin Franklin The Autobiography and Other Writings this quote appears on pages 68-69.

5. ^ Demolished date from:

George Morgan Hills, History of the Church in Burlington, New Jersey (Trenton: William S. Sharp, 1876) Page 321

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here6. ^ Biographical details of William Franklin's life and service as Royal Governor were drawn from a number of secondary sources, mainly:

• Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin, An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003)

• Larry R. Gerlach, New Jersey's Last Royal Governor (#13 in New Jersey's Revolutionary Experience series) (Trenton: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1975)

7. ^ William Franklin was actually appointed as the New Jersey Governor in September 1762, while in London.

He did not leave London to return to America until January 1763, arriving in Philadelphia on February 20.

On February 25, he came to Perth Amboy, where there was a ceremony when he took the oath of office.

On March 3, he came to Burlington, where there was another ceremony in his honor.

These events are chronicled in contemporary newspaper accounts from these months, which are reprinted in:

William Nelson, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, First Series, Volume XXIV (Paterson, NJ: The Call Printing and Publishing Co., 1902) Pages 103, 132, 136, 138, 139, 140, 144, 146, 147, 152-153 (A notice about Franklin's Sept. 5, 1762 wedding appears on page 104)

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here8. ^ Information for this section was drawn from:

"The Revolutionary Journal Of Margaret Morris Of Burlington, New Jersey, December 6, 1777, to June 11, 1778," reprinted in:

Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia Volumes IX - X, 1919-1921 (Philadelphia: Friends' Historical Society, 1921) Pages 2-14, 65-75, and 103-114

Available to be read at Google Books here

▸ A note that Margaret Morris lived in Green Bank appears on page 3.

This information also appears in the following book. The author claims to have visited Green Bank before it was demolished in 1873, and to have gone in the secret compartment where Joseph Odell was hidden:

George Morgan Hills, History of the Church in Burlington, New Jersey (Trenton: William S. Sharp, 1876) Page 321

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here

▸ ▸ "This morning a galley..." quote is not from Margaret Morris's diary. It is from a letter that she wrote to her sister Milcah Martha Moore on December 12, 1776. The text of the letter appears in a footnote on pages 10-11Margaret Morris's diary is highly recommended reading for anyone wishing to read a great firsthand account of a citizen whose life was affected by the Revolutionary War. During the course of researching this website, I have read many Revolutionary War letters, documents and diaries from the time period. Margaret Morris's diary is one of the best. Her writing is excellent, and her personality comes through very clearly, along with concern for her family and her Quaker faith.

9. ^ Information about Jonathan Odell was drawn from:

• Minutes of the Provincial Congress and the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey (Trenton: Naar, Day & Naar, 1879) Pages 211, 218, 219, 515-516, and 528 ("A person suspected of being inimical to American liberty" quote is on page 516)

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here• "The Revolutionary Journal Of Margaret Morris Of Burlington, New Jersey, December 6, 1777, to June 11, 1778," reprinted in:

Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia Volumes IX - X, 1919-1921 (Philadelphia: Friends' Historical Society, 1921) Pages 2-14, 65-75, and 103-114 ("The commandant seemed highly pleased..." quote is on page 7)

Available to be read at Google Books here• Cynthia Dubin Edelberg, Jonathan Odell: The Loyalist Poet of the American Revolution (Durnham, NC: Duke University Press, 1987)

• George Morgan Hills, History of the Church in Burlington, New Jersey (Trenton: William S. Sharp, 1876) Pages 307-323

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here

▸ Contains reprints of several original documents related to Odell, including three of his poems.• Winthrop Sargent, The Loyalist Poetry of the Revolution (Philadelphia: 1857) Pages 38-55

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here

▸ Reprints "The Word of Congress," a lengthy satiric poem by Odell which was originally published in the Royal Gazette on September 18, 1779.

10. ^ For architectural details about Old and New St. Mary's Churches, see:

National Register of Historic Places / Inventory - Nomination Form for the St. Mary's Episcopal Churches

Available as a PDF on the National Park Service website here11. ^ William S. Stryker, Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War (Trenton: Wm. T. Nicholson & Co., 1872) Page 67

Available to be read at Internet Archives here12. ^ Joseph Bloomfield; Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin; Editors, Citizen Soldier: the Revolutionary War Journal of Joseph Bloomfield (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1982) Pages 127-128, 136-137

13. ^ Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress

• One demonstration of Bloomfield's political prominence is that, at various times, he had reasons to correspond with each of the first four Presidents of the United States: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison.

Some of these letters are available to be read at the Founders Online / National Archive website:

• Letters written by Bloomfield can be read here.

• Letters received by Bloomfield can be read here.14. ^ See the Moses Bloomfield House entry on the Woodbridge page of this website for more information about Moses Bloomfield.

15. ^ For more information about the news of the signing of the Treaty of Paris reaching America on October 31, 1783, see the Princeton and Kingston pages of this website.

16. ^ Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress

Timeline of the United States Mint - United States Mint website

17. ^ Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-2005 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2005) Page 3

Available to be read at Google Books here18. ^ Information about Bowes Reed's military and political careers was drawn from:

• William Nelson, Editor, Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. III (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1906) Pages 415–416

Available to be read at Google Books here• William S. Stryker, Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War (Trenton: Wm. T. Nicholson & Co., 1872) Pages 35 and 354

Available to be read at Google Books here• Thomas F. Fitzgerald, Manual of the Legislature of New Jersey (Trenton: Thomas F. Fitzgerald, Legislative Reporter, 1917) Page 121

Available to be read at Google Books here19. ^ William B. Reed, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, Volume I and II (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston: 1847)

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here and here20. ^The Boudinot-Bradford House listing on the City of Burlington Historic District website states that the house was built in 1804. However, several other articles and books give other dates ranging back to 1798.

21. ^ Bard-How House listing on the City of Burlington Historic District website

22. ^ Minutes of the Provincial Congress and the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey (Trenton: Naar, Day & Naar, 1879) Pages 197 and 325

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here23. ^ References to John Lawrence as Mayor of Burlington in the 1760's can be found in the following contemporary and secondary sources:

• Four Dissertations, on the Reciprocal Advantages of a Perpetual Union Between Great-Britain and Her American Colonies (Philadelphia: William and Thomas Bradford, 1766) Page vi

Available to be read at Google Books here• William Stevens Perry, The History of the American Episcopal Church, 1587-1883, Volume I - The Planting and Growth of the American Colonial Church, 1587-1783 (Boston: R. Osgood and Company, 1885) Page 649

Available to be read at Google Books here• George Morgan Hills, History of the Church in Burlington, New Jersey (Trenton: William S. Sharp, 1876) Page 296

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here24. ^ Information drawn from these contemporary sources:

• "The Revolutionary Journal Of Margaret Morris Of Burlington, New Jersey., December 6, 1777, to June 11, 1778," reprinted in:

Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia Volumes IX - X, 1919-1921 (Philadelphia: Friends' Historical Society, 1921) Pages 2-14, 65-75, and 103-114 (The specific mentions of John Lawrence, sometime referred to as "J.L.", appear on pages 6, 7, 8, 106, and 107.)

Available to be read at Google Books here• Minutes of the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey (Jersey City: John H. Lyon, 1872) Pages 11, 12, 13, and 159

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here